|

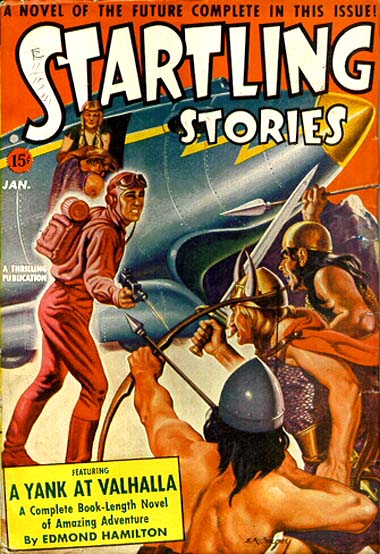

| [Original pulp from January 1941.] |

Part lost civilization fantasy, part science fiction, Hamilton plays with the idea that behind mythology lies a greater truth.

Physicist Keith Masters, during an exploratory survey flight, gets blown into a hidden area of the arctic where he discovers the secret lands of the Norse Gods.

|

| [An Ace double version from 1973.] |

Stylewise, the many typos (a pulp given) are unexpectedly balanced out by some lovely .50-cent word selections, and it's neat shifting gears as a reader between scientific terms and medieval descriptors. This integrated juxtaposition aside, a lot of the presentation is stirring with cries of "Our swords for Asgard!", impressive feasting hall settings, and saga worthy melees & martial battles.

|

| [UK re-titled version from 1950. And Freya's going to fall out of that top at any moment.] |

While the start isn't as fast as Lester Del Rey's The Day of the Giants (1950), they share a conceit that a mid-century modern man can think more clearly and problem solve better than an immortal, which here is still a false conceit, and one finds Masters a few times saying things like, "Score one for my science!" to convince us, but not successfully. Anachronistic of this, Masters flies a "rocket plane", which is more than bleeding edge technology in 1940, even for a well-funded polar expedition.

|

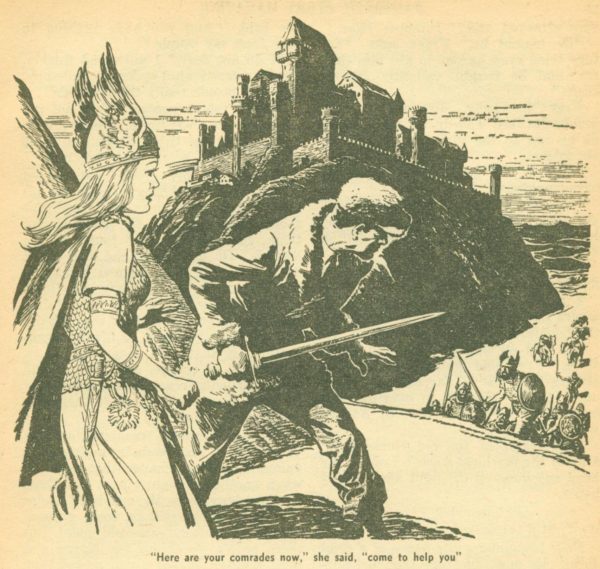

| [Interior art from Fantastic Story 1953 January pulp.] |

We suspect this early NorsePlay also possibly influenced Ian Cameron's Island At the Top of the World from 1961 where a polar foray stumbles onto a Viking civilization survival. And

the mix of high-tech with ancient dress reminds us of Stan Lee & Jack Kirby's Thor, which began in 1962, where the science is implied, but not overt, and one wonders if either of them read this beforehand.

|

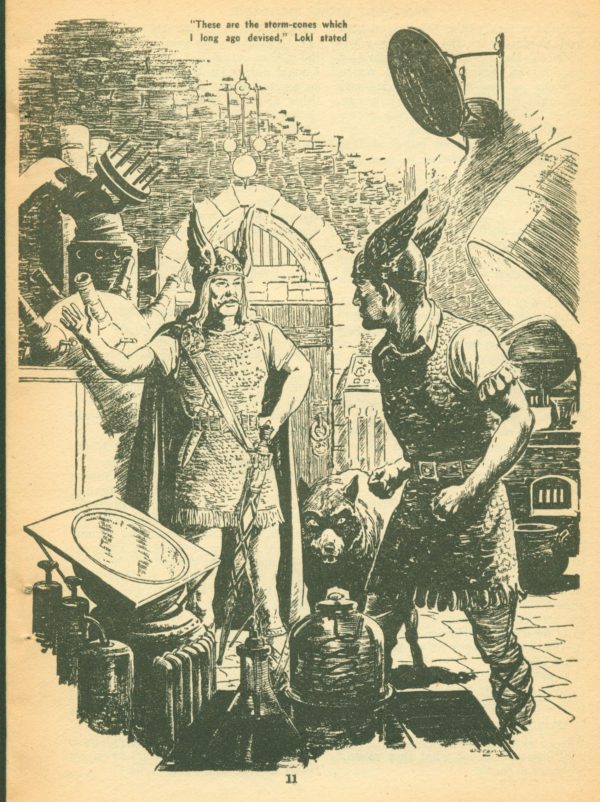

| [More interior art from Fantastic Story 1953 January pulp.] |

In terms of what was going on in 1940, we have an American character with no horse in the race between the Aesir & the Jotuns, getting involved for various circumstantial reasons in what may very well become Ragnarok. This raises the question if Hamilton possibly wrote this as an appeal for a U.S. entry into WW2. While the text always has the battles as being against the odds, the Viking ethos of combat being a necessary facet to support civilization and that risk being celebrated is prominent in the novella.

|

| [This same side-saddle valkyrie on colourless Bifrost art was also used for a later NorsePlay: Lester Del Rey's The Day of the Giants, except it was re-titled When the World Tottered.] |

With pulp motifs, A Yank at Valhalla also presents the idea of the hidden subterranean. Using the dwarves (here labeled the Alfings) and a radioactive Muspelheim as a pre-surface dwelling and advanced technological world, this presages The Shaver Mystery's pulps/memoirs by half a decade:

"This was no mere cavern, but an enormous hollow such as many have believed was left under the planet's surface by the hurling forth of the Moon." (p.96)

In a current young adult novel landscape of Riordan's Magnus Chase and Armstrong's The Blackwell Pages, where overweening teen sass underqualifies as optimism, going back to an early NorsePlay like Hamilton's A Yank At Valhalla yields more imaginative treasure.

# # #

Guillermo Maytorena IV knew there was something special in the Norse Lore when he picked up a copy of the d'Aulaires' Norse Gods and Giants at age seven. Since then he's been fascinated by the truthful potency of Norse Mythology, passionately read & studied, embraced Ásatrú, launched the Map of Midgard project, and spearheaded the neologism/brand NorsePlay. If you have employment/opportunities in investigative mythology, field research, or product development to offer, do contact him.

0 Comments